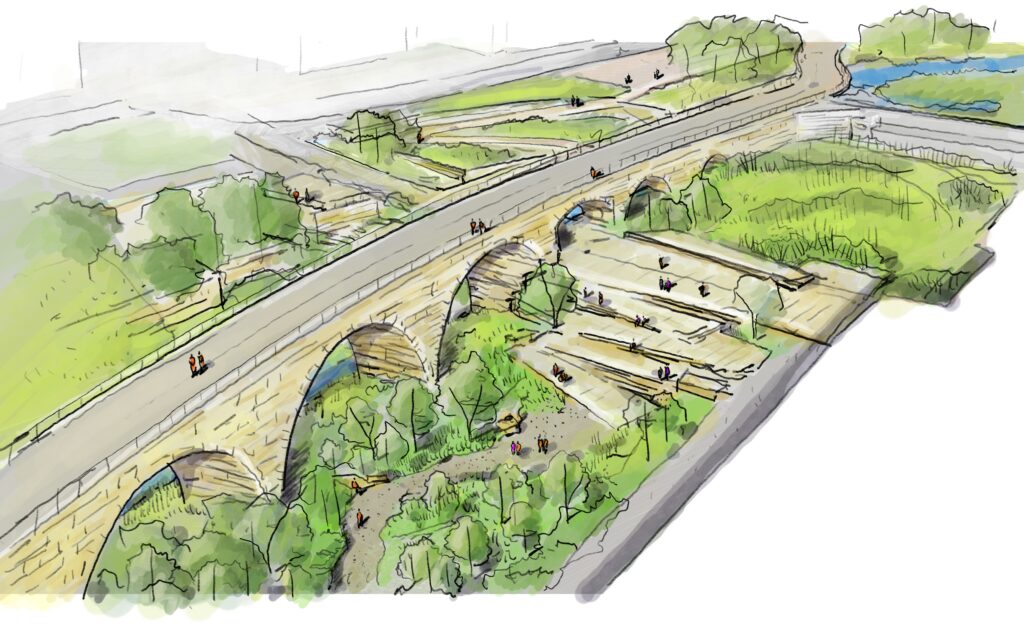

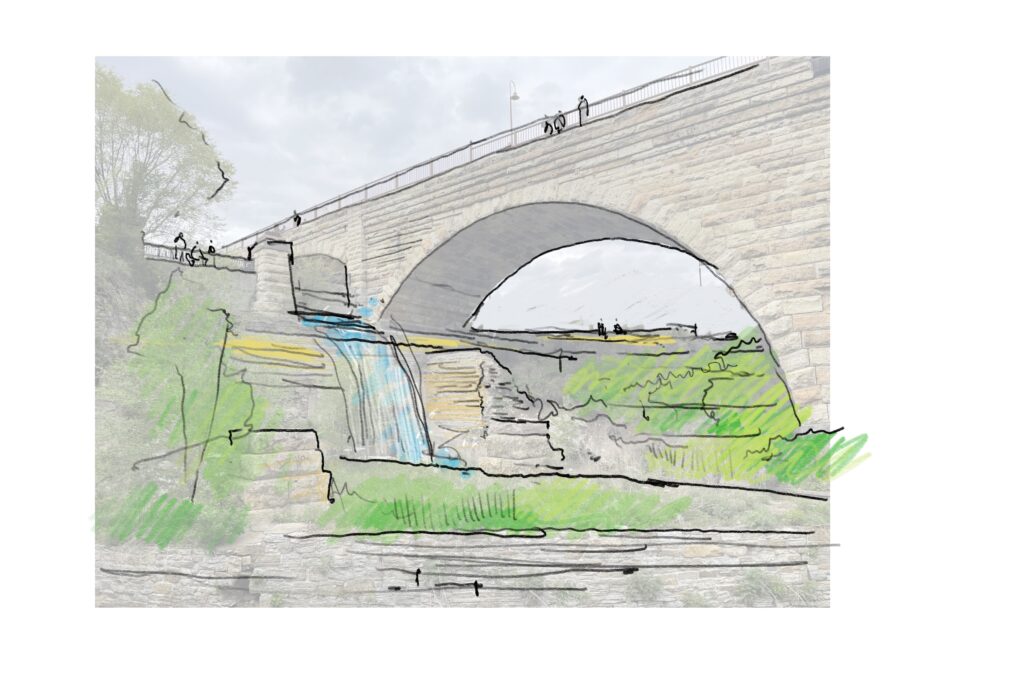

The layers of meaning, intentionality and care woven into the design can’t be conveyed fully through renderings or design drawings, but we can begin to tell the story by using Dakota language and sharing the design principles that shaped this work.

The Knowledge Keepers embedded Dakota values and perspectives into the design process at every turn. They shared cultural knowledge, oral history, relationships and an understanding of Dakota language that influenced every aspect of our work – from how meetings were structured to how team members were encouraged to learn Dakota language and integrate it into their deliverables. The resulting design is truly transformative.

From the start, Elder Glenn Wasicuna challenged the design team – architects, engineers, lighting designers, and permitting experts alike – to “think Dakota”. We also had to consider that “the land doesn’t know whether we intend to hurt or help it.” It is our responsibility to show the land the healing that is to come.

We constantly reframes our approach and the exploratory questions that drove the design process. Instead of imagining what we could make that would attract the most visitors or what we could build that would leave a lasting legacy, we asked:

- What does the River want?

- What is the land telling us, if we are patient enough to listen?

- What does the land need in order to heal? It needs Dakota people; it needs to hear its language.

- What can we give the land in return? If we take a rock, we need to give something in return – a gift or a story.

- What makes this place Dakota? Is it how it looks or how it feels?

- How can we show the world that the power of Owámniyomni is still here?

- A century ago, what would the turbulent waters of Owámniyomni have sounded like? How can we make the water roar now?

These questions and more informed the project site plan, materiality, procurement strategy and other aspects of restoration.