By Eric Roper for Star Tribune

A giant hidden concrete wall buried deep below the Mississippi River has been holding the storied St. Anthony Falls in place for more than 140 years. It safeguards Minneapolis’ water supply and helps ensure the river doesn’t undermine bridges or other infrastructure.

But the wall’s condition is largely a mystery. Now some river experts and politicians are calling for a closer examination, fearing that a failure of the aging structure could prove catastrophic.

“There’s a dramatic threat to the Twin Cities — water supply, upstream infrastructure, downstream navigation, billions in central riverfront development,” said John Anfinson, a leading Mississippi River historian who has been calling attention to the issue. “How serious is it? We don’t know.”

The problem is the wall is largely inaccessible, lodged in sandstone beneath the riverbed. And it is unclear who is responsible for it; none of the entities most closely associated with the falls believes they are the owner.

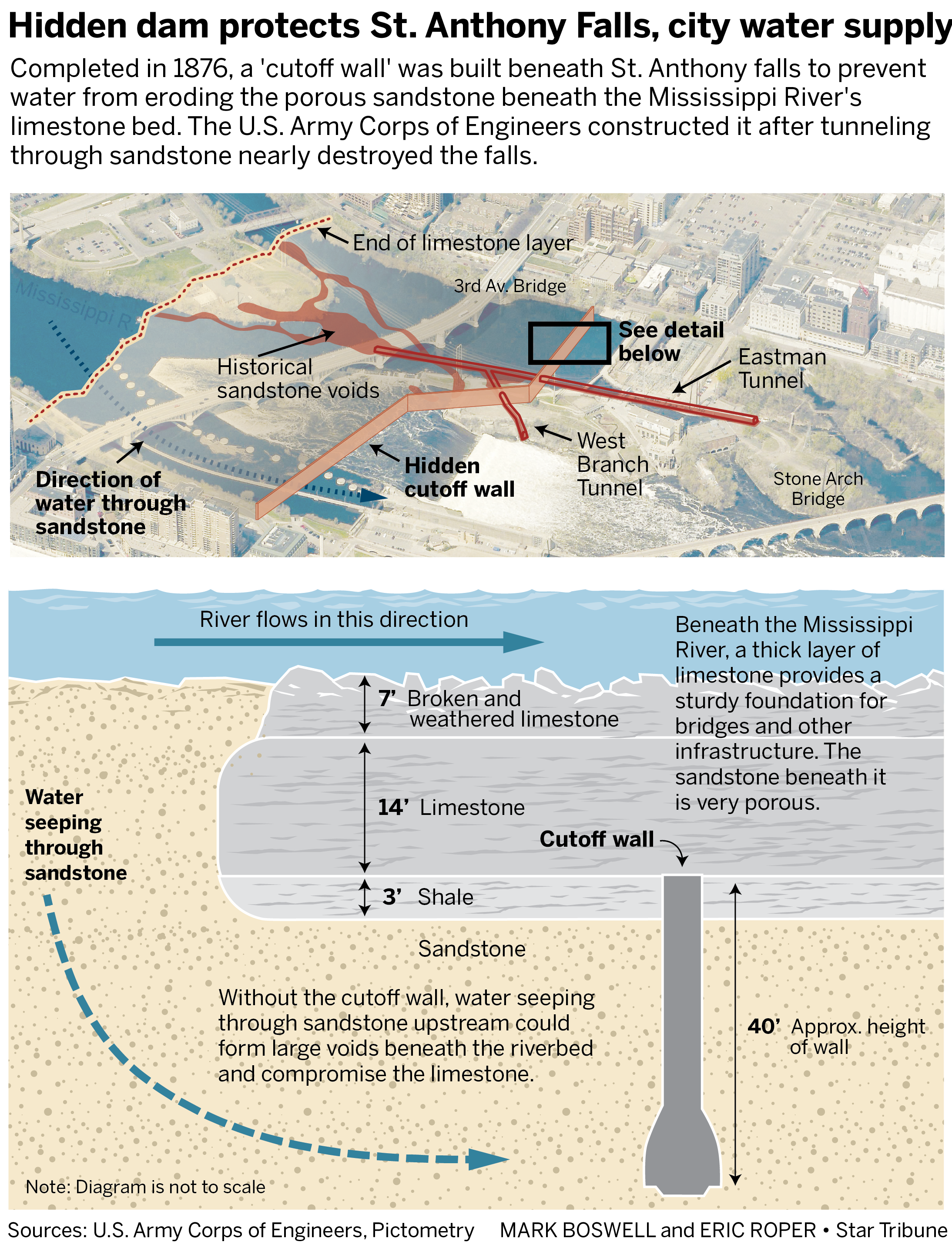

Roughly the height of a three-story building, the wall helps prevent the collapse of a thick limestone riverbed slab by stopping flowing water from eroding soft sandstone underneath it. It was constructed after one of the biggest disasters in Minneapolis history, when a tunneling project went awry and nearly destroyed the falls in 1869.

There is no firm evidence that the wall, often called the cutoff wall, is in danger. But the vast majority of it can’t be seen, except for an area where it intersects with old tunnels.

Anfinson has been trying to alert public officials about the issue before the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — which built the wall — exits the area after the lock and dam closed to navigation in 2015.

The issue has piqued the interest of officials ranging from Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey to U.S. Rep. Ilhan Omar, both of whom want the Army Corps to conduct a closer examination.

“If history’s taught us anything, it’s that we need to be proactive when it comes to critical pieces of infrastructure like the cutoff wall,” Frey said.

The Congressional Research Service is investigating the legal process that would need to occur for the corps to analyze the wall’s condition.

Anfinson has written extensively about the history of the riverfront. He says he felt obligated to speak out as someone well-versed in the wall’s history. And he’s thought about the questions now being asked after the Florida condominium collapse in June.

“Who knew what and when? And what did they do about it?” Anfinson said. “This wall may last another 144 years. But how do we know if we haven’t done a good study of it?”

Anfinson once worked for the corps, though he is not an engineer. He later joined the National Park Service, where he became superintendent of the national park spanning most of the Mississippi River in the Twin Cities. He retired in January.

Nan Bischoff, a corps project manager, said people are raising a lot of concerns over something that is not actively threatening. Bischoff said the wall is effectively insulated by all the material and infrastructure that surrounds it.

“It’s not going anywhere,” Bischoff said. “There’s no place for it to go.”

A disastrous lesson

The falls likely wouldn’t exist today without the man-made infrastructure designed to halt erosion. In its natural state, the falls inched upstream roughly 4 feet per year because water tumbling over the edge of the limestone riverbed would wash away the exposed sandstone at the foot of the falls. This caused the limestone on top to collapse and the falls to recede. White settlement took root in Minneapolis just before the gradually moving falls ran out of limestone upstream. The falls soon fueled a booming riverfront milling industry.

Attempting to generate power on Nicollet Island in the 1860s, industrialist William Eastman and partners bored a deep tunnel through the sandstone. But it flooded during construction, washing away large amounts of sandstone and causing portions of the limestone above it to collapse. The city’s natural power source was suddenly in jeopardy. It took the corps about two years to erect a concrete barrier in the sandstone to halt further erosion. Completed in 1876, the wall is 6 feet thick at its base, roughly 40 feet tall and spans 1,850 feet across the river.

Upon Eastman’s death in 1902, the Minneapolis Journal wrote that his mistake had taught the city a valuable lesson about the fragility of the falls. “Until he made that excavation no one knew of the percolating rivulets that were waiting only the slightest invitation to become gushing torrents and vent the waters of the whole river through the soft sandstone” and destroy the falls, the paper wrote.

Sporadic monitoring

The wall is now an integral but invisible component of St. Anthony Falls — standing deep below the horseshoe-shaped dam visible from the Stone Arch Bridge.

There have been sporadic attempts over the years to assess the wall’s condition. Xcel Energy began monitoring water pressure above and below the wall in the late 1980s, for example, to assess its performance. But that stopped in 2001 — with the approval of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) — after data revealed the equipment was not working correctly.

Two of the Eastman-era tunnels, one man-made and the other scoured by water in the disaster, intersect with the cutoff wall. The man-made Eastman Tunnel contains so much sediment that inspectors in 2009 could not reach the wall. The other, known as the West Branch Tunnel, is still passable. Xcel, which owns a lot of infrastructure at the falls, now inspects the tunnels downstream of the wall every 10 years — the upstream areas are not accessible. The power utility inspected them annually in the early 2000s but ultimately persuaded FERC to reduce the required frequency, according to public correspondence between the entities.

FERC spokeswoman Celeste Miller wrote in an e-mail that the last tunnel inspection in 2019 showed “the wall was in good condition.” The agency later clarified that only a sliver of the wall was visible.

But representatives for Xcel said their engineers do not inspect the cutoff wall. “Our engineers have not seen anything of concern that would impact the safety of our hydroelectric generation,” Xcel spokeswoman Julie Borgen wrote in an e-mail.

The public cannot see the dam safety reports containing those inspections, however, because FERC classifies it as Critical Energy/Electric Infrastructure Information. FERC requested that the Star Tribune sign a nondisclosure agreement to see them, something the paper generally does not do.

The corps in a 2015 report assessed more than 30 ways that the falls could be compromised, four of which were considered “risk-drivers” warranting further analysis. One of those risk-driver scenarios involved water eroding tunnel walls, causing a break in the limestone above and then damage to the cutoff wall. This accelerates the erosion and undermines a key nearby dam, leading to further problems.

The report concluded that the likelihood of this scenario was “remote” and that it would happen slowly enough for the problem to be fixed. But the confidence in that assessment was low, in part because there is limited information about the condition of the wall and the tunnels. University of Minnesota Civil Engineering Prof. Joseph Labuz, who examined the 2015 report at the Star Tribune’s request, said more data about water pressure around the wall would help assess its condition. Concrete is strong under compression, he noted.

“The wall is surrounded by sandstone,” Labuz said. “And you have to have a lot of removal of the sandstone for this wall to be compromised.”

Worst-case scenarios

If key infrastructure at the falls were compromised, Minneapolis could find itself without access to water — at least temporarily. The dams at St. Anthony Falls raise water levels upstream, where Minneapolis draws its drinking water. The city has roughly three days of water in reserve.

More than drinking water is at stake. Anfinson noted that corps documents say an undermining of the falls would turn that steep drop into rapids extending far upstream of downtown — putting bridges and dams at risk.

“A worst-case scenario for the cutoff wall would be catastrophic for the roads and bridges surrounding it, for countless residents and businesses on the riverbanks, and for the drinking water supply of nearly a million people,” Omar said in a statement.

Residents got a glimpse of the river’s destructive power in 1987, when water eroded the sandstone beneath an Xcel Energy hydroelectric plant downstream of the Stone Arch Bridge. It washed away the plant’s foundation and the 90-year-old plant collapsed.

Anfinson credits the corps for building a wall that has lasted for nearly 145 years. But nature is persistent, he added.

“For 12,000 years, nature was trying to end St. Anthony Falls — slowly backing it up the river,” Anfinson said. “It got so close, and we stopped it. Do you think nature has surrendered to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers? I don’t think so.”