By Auds Jenkins, Star Tribune.

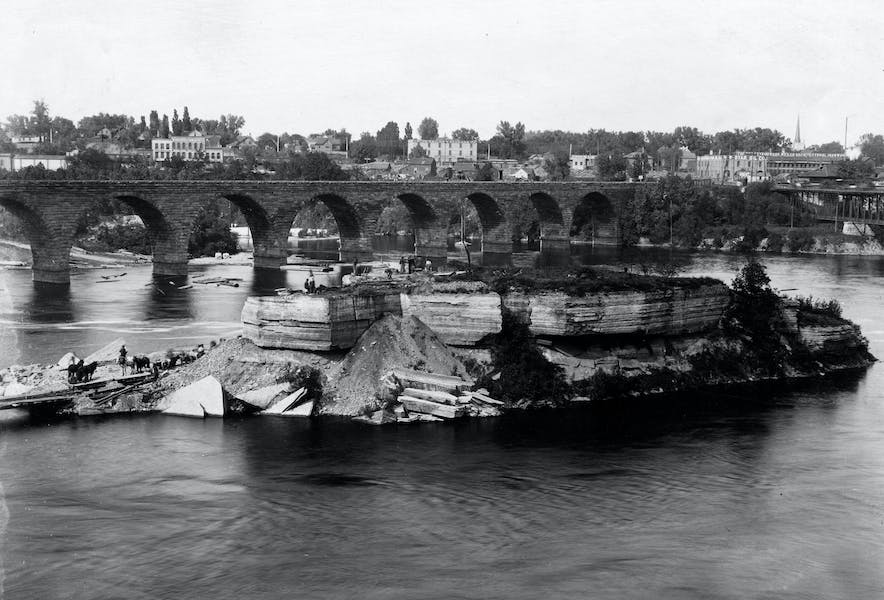

Spirit Island was once a prominent landmark of the downtown Minneapolis riverfront.

Visitors to Minneapolis’ Stone Arch Bridge often gaze at the St. Anthony Falls, the downtown skyline or the area’s famous flour mills.

But when reader Carol Roos crosses the bridge, her eyes are drawn to what’s not there.

Just downstream from the falls is the empty space in the Mississippi River once occupied by Spirit Island, a sacred site for Dakota people. It gradually disappeared between the 1890s and the 1960s as it was quarried for limestone and then dredged to further navigation of the river.

A retired librarian and longtime Marcy-Holmes resident, Roos first heard about Spirit Island in one of her university classes. Her appreciation for it deepened in 2017 when she saw a video projection of the island at the Upper St. Anthony Lock and Dam as part of Northern Lights’ “Illuminate the Lock” program.

“We cannot see Native culture the way it was when [European settlers] came, but to honor a space that has been desecrated is so very important,” Roos said.

Roos turned to Curious Minnesota, the Star Tribune’s reader-powered community reporting project with a request to tell the history of Spirit Island.

Sacred history

Long before Europeans settled in the area, the falls and the surrounding islands were sacred Dakota sites. St. Anthony Falls (Owámniyomni) and Spirit Island (Wíta Wanáǧi) were places for ceremonial practice and honoring the cycle of life and death.

“The area itself was a really important place for Dakota people. They would go and gather there, they would pray there,” said Shelley Buck, president of Friends of the Falls and a Dakota woman of the Prairie Island Indian Community. “And unlike what religions do, where people go to churches or synagogues or places of worship to do their worshipping, for my people, the outdoors is where we worship.”

Some Dakota women would go to Spirit Island to give birth. Buck also recounted oral histories of the area around the island that tell of a grieving Dakota woman who took her offspring, went over the falls and died in the river below when her husband took a second wife.

“Like most things in our culture, everything is a circle,” Buck said. “And so you have birth there, but you also have death there.”

Historical newspaper accounts attributed the island’s English name to this anecdote. But a spokesperson for Friends of the Falls, Amanda Wigen, said not all Dakota oral histories make the same connection.

“By nature, oral history varies based on the speaker, their experience and their perspective,” Wigen said.

‘The (paddle) wheels of progress’

The river’s natural elevation drop at the falls would ultimately make this portion of the Mississippi River an industrial hub, leading to the destruction of Spirit Island.

Lumber milling arrived on the riverfront in the mid 1800s. By 1880, Minneapolis had become the “Flour Milling Capital of the World” by harnessing power from the river.

The flour milling industry rocketed Minneapolis into a period of unprecedented growth. The city’s population grew twelve-fold in 20 years, reaching 165,000 by 1890. To manage this influx of people, settlers began quarrying Spirit Island for limestone.

“The city is booming so great with the lumber and flour milling, the construction can hardly keep up with it,” said John Anfinson, an environmental historian who specializes in the upper Mississippi River area. “So if they can get limestone as foundation for a building or for part of the construction of a building and there’s an island sitting out there in the river that they can easily take it from, they’ll do it.”

Anfinson estimated that quarrying had eliminated all but a sixth of Spirit Island by 1899. In January of that year, the Minneapolis Tribune described the dismantled island as “that beauty spot of nature which has so recently disappeared by the uncompromising hand of man, to make room for the (paddle) wheels of progress.”

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began removing what was left of the island in 1960 to ease commercial navigation of the river. The Upper St. Anthony Lock and Dam would soon allow boats to navigate upstream of the falls.

By 1963, Spirit Island was gone.

A new beginning

The Upper Lock was closed to commercial navigation in 2015 to stop the spread of invasive carp. In the years since, local groups have been discussing the future of the area around falls, including the spot where Spirit Island once was.

Under Buck’s leadership, Friends of the Falls is working with the Native American Community Development Institute to reimagine St. Anthony Falls. Potential plans unveiled in early 2023 included native landscape restoration, walking paths and ceremonial gathering places that honor the sacred nature of the site.

Many see it as a new beginning, one that must be shaped by both Native and non-Native voices.

For some local leaders, remembering Spirit Island is a critical piece of the project. The island may be physically gone, Buck said, but its spirit remains.

“It’s still an important place to my people. It’s a place where some of our people go to pray and give thanks even to this day,” Buck said. “So it’s not something of the past, or ‘ancient history’ like they like to call it. It’s something of the here and now.”

Read the story at StarTribune.com.