By Owámniyomni Okhódayapi | February 8, 2024

Dakota people, historically hunters and gatherers, sustained themselves through a rich and versatile diet long before European colonization altered their culinary landscape.

But there was more to traditional Dakota diets than just hunting game and gathering wild plants. Dakota people were also farmers; they made use of resources in creative ways and often ate food purposefully. When considering “Native American” cuisine, fry bread springs to mind for many people. However, it’s important to recognize that fry bread is a byproduct of colonization, as are the resulting prevalent health issues among Indigenous peoples, such as diabetes. Today’s blog post explores the traditional foods of the Dakota people, shedding light on the impact of colonization and the subsequent challenges faced by Indigenous communities, particularly in terms of health and food insecurity.

Pre-Colonization

Prior to the arrival of European settlers, Dakota peoples had a diet that supported their lifestyle and kept the community healthy. Bison herds provided a consistent source of meat , complemented by other plains mammals, fish from lakes and rivers, and a commitment to utilize every part of the animal for minimal waste.

While meat was an important part of the Indigenous diet, plants grown and gathered made up the majority of an Indigenous diet. There are a variety of wild fruits and vegetables indigenous to Mni Sota – things like blueberries, gooseberries, elderberries, plums, wild rice, and much more.

Indigenous gatherers didn’t rely only on wild growing plants; they were well known for growing the three sisters. The three sisters consist of corn, beans, and squash, all of which aid in each other’s growth. Corn offers towering stalks for beans to ascend. Beans contribute nitrogen to enrich the soil and offer structural support to the tall corn in the face of strong winds. The expansive leaves of squash plants serve to shade the ground, aiding in soil moisture retention and weed prevention. The symbiotic relationship between these plants showcased the ingenuity of Indigenous agriculture, promoting sustainability and maximizing yield.

The Impact of Colonization

Colonizers sought to displace Indigenous peoples by disrupting their access to traditional foods, including the strategic targeting of bison herds and forced removal from homelands.

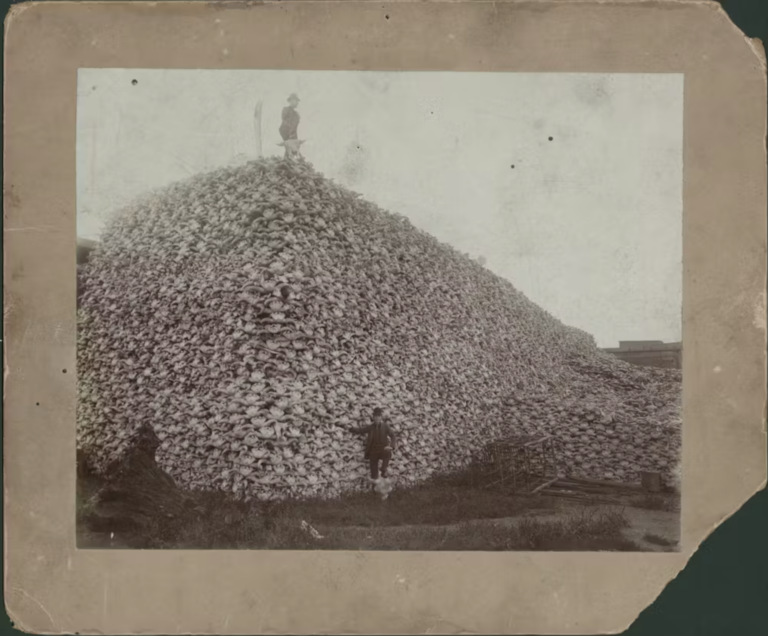

Men standing with pile of buffalo skulls, Michigan Carbon Works, Rougeville MI, 1892. Photo from Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

You might be familiar with this popular image of a man standing with a mountain of bison skulls. It’s been said that at the end of the 18th century there were between 30 and 60 million bison on the continent, yet at the time of this photo, 1892, their population was reduced to only 456 wild bison.

In the wake of forced changes to their diet initiated by the U.S. government in 1851, Indigenous peoples were provided rations, commonly consisting of things like wheat flour, sugar, and lard. From these ingredients Indigenous people learned to make food to survive on – things like the now well known frybread. This shift from their traditional diet and lifestyle led to a drastic shift in the overall health of Indigenous communities. Over the past 100 years there has been a significant increase in obesity among Indigenous people, as well as Type 2 Diabetes. According to a study published by the American Diabetes Association, one in six American Indian and Alaska Native adults has been diagnosed with diabetes. This rate is more than double the pervasiveness of diabetes for the general U.S population. This stark difference underscores the profound implications of historical dietary disruptions on the health and well-being of Indigenous communities.

Where Indigenous Food Stands Today

In recent years we’ve seen Indigenous food revitalization programs become more mainstream. From the Sioux Chef and their restaurant Owamni, specializing in Indigenous cuisine to, Indigikitchen, an online cooking show dedicated to re-indigenizing our diets using digital media.

Despite the increased emphasis on Indigenous food practices in recent years, studies reveal that 25 percent of American Indians and Alaska Natives consistently face food insecurity—twice the rate observed among white Americans. This challenge can be attributed, in part, to the isolation and rural nature of many Native reservations, leading to elevated costs for various food items. Notably, apples are about 30 percent more expensive in Indian Country. Paradoxically, certain unhealthy foods are more affordable than the U.S. average, as indicated by a separate analysis from the First Nations Development Institute, which found that the average price of Cheetos on reservations consistently falls below the national average.

While we push forward with Indigenous food revitalization we must not forget our relatives in rural and isolated communities with limited resources and access to traditional foods and practices.

If you would like to support the work of Indigenous food sovereignty, please consider donating to, volunteering for, or promoting the following organizations:

“The mission of Dream of Wild Health is to restore health and well-being in the Native community by recovering knowledge of and access to healthy Indigenous foods, medicines and lifeways.”

“Founded in 1988, the Cheyenne River Youth Project is a grassroots, Native- and woman-led nonprofit organization dedicated to providing Lakota youth with access to a vibrant and more secure future. At the heart of our innovative, culturally relevant work is Wólakȟota, our people’s sacred way of life.”

Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance

“We are an organization dedicated to restoring the food systems that support Indigenous self-determination, wellness, cultures, values, communities, economies, languages, and families while rebuilding relationships with the land, water, plants, and animals that sustain us.”

“Our mission is to promote Indigenous foodways education and facilitate Indigenous food access.”